People complain that we are too quick to put our heroes “on a pedestal.” Normally this phrase isn’t literal. For the Syrian saint Simeon Stylites, it was. “Stylites” isn’t his last name; it is a title or nickname roughly meaning “Pillar-man” because he spent the last decades of his life living on a small platform on top of increasing tall pillars. If putting someone on a pedestal is a problem, what do we do with someone who literally put himself on one that was sixty feet high?

The Early Life of Simeon Stylites

Simeon grew up in poverty in a shepherd family in fourth-century Syria (then part of the Roman Empire). Perhaps due to his childhood hardships, he considered the normal simplicity of the monastery he joined to be too easy. After he insisted on fasting from all food for a full week, wearing rough palm belts that tore his skin, and other extreme acts of self-denial, his community asked him to leave. Then, as a hermit, he spent the entirety of Lent bricked into a small hut without eating or drinking. A priest who supported him found Simeon half-dead at Easter and nursed him back to health.

Simeon decided that the experiment had been a great success. He continued to spend every Lent in that manner and tried other feats of renunciation such as tying himself to a post to remain upright all Lent (standing was the normal posture for prayer in ancient Christianity before kneeling replaced it). This impressed enough people that Simeon began to be bothered by the amount of visitors interrupting his prayers.

Climbing the Pillar

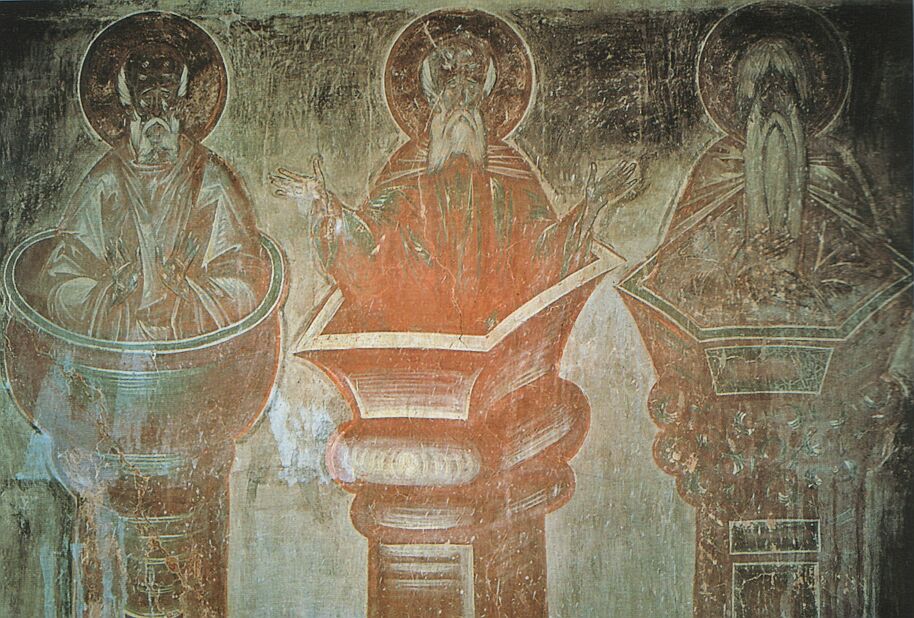

So Simeon built a little platform on top of a short pillar to give himself some space for prayer and so he could preach to larger crowds when appropriate. He never left the pillar. Instead he hauled up his scant food and water with a rope and had a ladder nearby for a few visitors to come up.

This life attracted even larger crowds, especially Arab Bedouins and other desert pastoralists. Simeon preached to these visitors, converted many of them, and performed miracles. As crowds grew, he went to even taller pillars and more extreme ways of punishing his body. By his death, he had mastered the art of staying upright in prayer for the forty days of Lent without any support, without food or water, and with an infected ankle crawling with maggots.

A Difficult Saint for Me

I don’t like Simeon much. I admit his life touched others and brought them closer to God. I also admit that both the Bible and tradition recommend Christians fast and do penance as part of their spiritual discipline and strengthening. Simeon, however, just seems so extreme. More external suffering doesn’t necessary equate to greater interior holiness. His life almost makes it look like suffering rather saintliness was the point.

I worry that Simeon’s kind of life is too attention-seeking, like a prideful and very painful way of saying, “Look at me! I’m special!” I worry too that such a life of extreme mortification quickly becomes “Pelagian” (the heresy of relying solely on yourself for salvation instead of God’s grace). Besides all that, Simeon once used his fame to protest synagogues being returned to Jewish worshippers. Anti-Judaism was common among both Christians and pagans at the time, but is abhorrent to my modern values.

Simeon’s Critics

I’m not alone in my initial reaction to Simeon. Western Christians never seemed to warmed up to him. His January feast day failed to make the official Roman calendar of celebrations even before Vatican II. The 1912 Catholic Encyclopedia article on him slips in a couple snarky comments such as noting that Simeon’s first monastery kicked him out “perhaps not unwisely.”

Eastern Christians have traditionally admired Simeon, but not without controversy even there. Despite inspiring a small forest of imitators on their own pillars, he faced contemporary criticism. Theodoret, one of Simeon’s followers, wrote a sometimes defensive biography of the saint. He urged “fault-finders to curb their tongue[s]” (c. 12, trans. R. Pearse) and scoured the Bible for justifications of Simeon’s lifestyle. A century later, the historian Evagrius also testified to that unease when he wrote that the local bishops and abbots had worried that diabolical pride inspired Simeon’s life. They dispatched a messenger to order Simeon to come down from his pillar; only if Simeon had the humility to obey the church authorities would he prove the suspicion false and be allowed to resume his life. Evagrius says Simeon passed the test.

Not a Tame Lion

So why write about this ancient, strange Syrian? In C.S. Lewis’ The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, the children ask if meeting Aslan, the great lion that is a painfully obvious metaphor for Christ, is “safe.” No, they are told, Aslan is certainly not safe, but he is good. Jesus is not a tame lion.

There is always a temptation in religion to domesticate God. We want to make him a comfortable figure that fits all our preconceptions. Such a God who never challenges us and simply makes us feel good is comforting in a shallow way. With that God, we’re always right and never have to change. But we never grow. And then we start to wonder why we need a God in the first place if we’re the one’s in control of him.

So maybe it does make sense to consider God’s saints that don’t fit my domesticated vision of God. According to his contemporary admirers, Simeon bore good fruit. His extreme life let him preach effectively to those who would have ignored the quiet and sensible. His position between heaven and earth was not so much placing himself above others as giving him a platform (literally) to speak words others needed and to intercede for them in constant prayer. That interpretation of him can’t be lightly brushed aside.

The Challenge of Simeon’s Sanctity

Simeon scares me. If I put aside my initial reaction and consider that other Christian supporters of him could be right, then I’m forced to ask myself uncomfortable questions. As Theodoret and others said, Simeon’s Lenten fasting and standing would have killed any person unless a miracle happened. Does that mean God wants that kind of extreme penance? I have trouble doing a day without solid food. Or, beyond food, how quick am I to fill my free time with entertainment, reading, or even busywork? If Simeon is a saint and an example to follow, do I need to start giving up some of my comfortable, pleasurable routines to focus more on prayer and spiritual work?

If Simeon’s biographers are right about his humility, then that also raises uncomfortable questions about why I’m suspecting others of pride. It’s easy to find an excuse to dismiss people who are following God a different way than I do. Ironically, my temptation to accuse Simeon of pride is a sign of my own struggle with pride. I want to say I’m right and others whose life challenges me are wrong. If I do that all the time, however, how can I learn new ways of growing? And how can I love my brothers and sisters who probably are trying their best to follow God if I’m busy judging them?

I still have trouble admiring Simeon. Perhaps I’m just not ready for his example of sacrifice. I am not about to run out and adopt his or other people’s ideas of how to live just because I might be wrong. I do think, however, that I need saints like Simeon. I need saints that don’t fit comfortably into my life. I need that challenge to be humble and, even when someone puzzles me, to love them.

Hi Dr. Eric,

I really enjoyed learning about Simeon. I had never heard of him before. I think I will pray to him to help me to become more disciplined.

I’m fasting from TV and social media. I decided to give up social media Monday-Saturday. I decided to give up TV until sundown. I’m trying to choose God more over those two activities. Simeon will help me for sure!

I’m going to recommend this blog to a few folks who I think will enjoy it. Thank you for sharing your writing with us.

Thank you! I’m glad you’re finding it worthwhile. Good luck with the fasting–it sounds like a fruitful plan.

Not a fan of Simeon either, but strangely interesting and eye opening to others unique ways of bearing fruit.

Thanks!