Feast Day: June 22

When Sir Thomas More ascended the scaffold to die, he joked with his executioners, asking them for a hand up—and adding that he would be happy to see himself down. It’s the kind of story that would sound apocryphal for most people, but it fits St. Thomas’ gently impish sense of humor. Maybe Thomas More’s humor isn’t that surprising. In addition to being a martyr, lawyer, government leader, and one of the most learned men in England, he was a father who loved his children so much that he adopted more to share the love. His humor might have been more sophisticated than the typical dad joke, but he lived in the time before computers. You had to work at humor then—you couldn’t just look up new jokes in an online dad-a-base.

I apologize in advance: there are a few dad jokes scattered throughout this post, but I guess you’ve realized that. Dad jokes are always apparent. Of course, there is more to St. Thomas More, martyr and father, than jokes, whether good or bad.

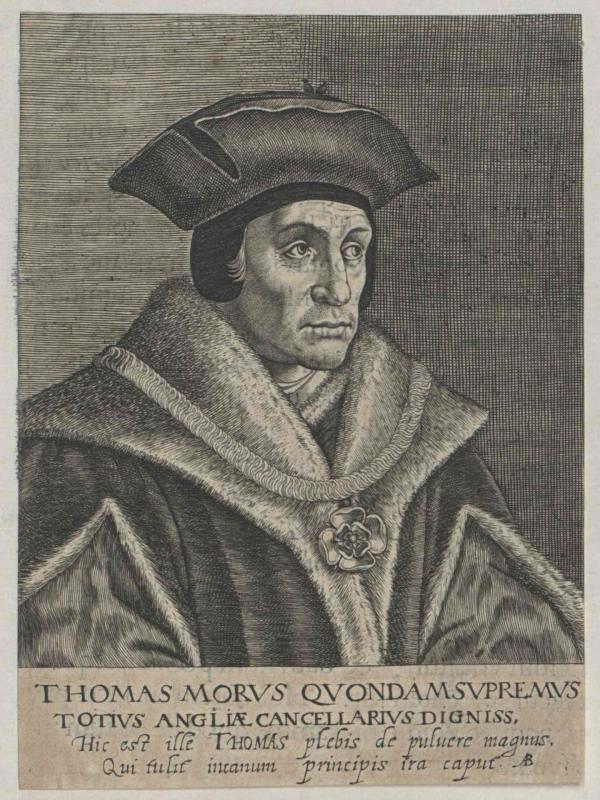

The Life and Death of Thomas More

When St. Thomas More climbed the steps to the scaffold, he did so willingly (despite knowing that you shouldn’t trust stairs—they’re always up to something). Born in 1478, he profited from the best Renaissance education that London and Oxford could provide. Although he flirted with joining a Carthusian monastery for several years, he eventually followed his lawyer father’s footsteps into the legal profession. You might say that his dad was also his father-“in-law”.

Thomas soon gained international fame thanks to his insight, learning, and wit. His writings (most famously the satirical Utopia) earned acclaim for his thought-provoking and entertaining calls for virtue. Despite that, he became a politician. He served first as an English representative hammering out commercial and political disputes with the French, and then the government kept asking him to do more. Eventually he received the office of lord chancellor, becoming King Henry VIII’s top advisor.

Then Henry decided he wanted to separate from his current wife and marry his mistress. This violated Catholic teaching about the sacrament of marriage, but Henry managed to solve that little problem by declaring that he and his entire country were no longer Catholic. Thus England joined the burgeoning Protestant Reformation.

It is one thing for the government to decree that people should act or believe in a certain way; it is another to make them. Many English men and women remained faithfully Catholic, including Sir Thomas. He tried to avoid trouble. When he could no longer support government policy, he quietly resigned. He stayed at home, out of politics, careful not to speak directly against the king or his new queen. Presumably he also would have said nothing against the other four women that Henry went through, but Thomas’ head would fall to Henry’s axe a year before the king tired of his new queen and sent her to the chopping block. Even though Thomas said nothing, his quiet refusal to cooperate with the government’s wrongdoing attracted attention and gave others courage as they struggled with their own consciences. Perhaps Henry’s outrage can be explained by the uncomfortable spur of his own conscience awakened by his former political servant. In the end, Henry found men willing to manufacture false testimony accusing Thomas of speaking treasonous words. So, through the perversion of the judicial system that Thomas More had spent much of his life serving, Henry arranged Thomas’ imprisonment and death.

“Although I know well, Margaret, that because of my past wickedness I deserve to be abandoned by God, I cannot but trust in his merciful goodness. His grace has strengthened me until now and made me content to lose goods, land, and life as well, rather than to swear against my conscience… I will not mistrust him, Meg, though I shall feel myself weakening and on the verge of being overcome with fear. I shall remember how Saint Peter at a blast of wind began to sink because of his lack of faith, and I shall do as he did: call upon Christ and pray to him for help. And then I trust he shall place his holy hand on me and in the stormy seas hold me up from drowning…

Sir Thomas More’s final letter before his execution, to his daughter Margaret. July 5, 1535.

“And, therefore, my own good daughter, do not let your mind be troubled over anything that shall happen to me in this world. Nothing can come but what God wills. And I am very sure that whatever that be, however bad it may seem, it shall indeed be the best.”

Thomas More the Dad

Catholics commonly honor Thomas More as the patron saint of lawyers, judges, and politicians; some also know him as the patron saint of adopted children and their parents. He had three daughters and a son with his first wife. After she died, he married a widow and gained a stepdaughter. He then agreed to serve as guardian for two other girls, distant relatives in difficult circumstances. All three adopted daughters received the same affection and education as his biological children—and he shocked his contemporaries with the full humanistic education that he gave them all even (gasp) the girls. Erasmus, the leading humanist intellectual of his day, was shocked and impressed to discover that his work had been translated into English by a woman: Margaret Roper, Thomas’ daughter.

Thomas often had to be away from his family on government business. He always wrote and gently teased his children. In one, he declares his son John as temporarily his favorite child since he has been writing his father every day. His other children are supposed to laugh… and then take the time to write! In another though he tells Margaret not to have so “much bashfulness and timidity” in asking for money; he is a father who loves to give and who trusts that his children are good enough not to abuse it. He writes back in loving trust to her “whom virtue and learning have made so dear to my soul. So the sooner you spend this money well, as you are wont to do, and the sooner you ask for more, the more you will be sure of pleasing your father.”

“Virtue and learning”—these are not throwaway words. Education means everything to Thomas. In one of his affectionate letters to his children, he jokingly addresses it “to his whole school” and begins, “See what a compendious salutation I have found, to save both time and paper, which would otherwise have been wasted in reciting the names of each one of you.” Naturally one shouldn’t waste paper—it’s tear-able. His teasing continues, but with a point. “I hear you are so far advanced in that science that you can not only point out the polar-star or the dog-star, or any of the constellations, but are able also—which requires a skillful and profound astrologer—among all those leading heavenly bodies, to distinguish the sun from the moon!” He’s not the sort of father who, when asked by his boy if he could tell him what an eclipse is, would simply say, “No sun.” He values all types of knowledge.

Thomas is also a father who knows that taking the time to distinguish the sun and moon is not always common. It’s so easy to be dazzled by one thing and forget another, or to get lost in the thickets of the complex and forget the simple path. He has seen too many leaders leave behind the basic virtues that make living worthwhile. Virtue, in his view, is the whole point of education. So he warns his children “to raise your mind also to heaven, lest the soul look downwards to the earth, after the manner of brutes, while the body looks upwards.” Learn the truth about the world to learn the truth about God. Then live that truth.

What a Father is For

It cannot have been easy for Thomas to choose his conscience at the end knowing that he would have to say goodbye to his children and his grandchildren, at least in this world. Yet knowing that his family watched him also made betraying his faith and values practically impossible to contemplate. Thomas cared for his children. He wanted them to have every advantage in life—education, money, and everything else; but most of all, he wanted them to be good. The best gift he could offer them was to help them live as children of their Father in heaven. As a man finely-tuned to the detection of hypocrisy, he knew that his actions and example mattered more than his words no matter how beautiful or witty they might be.

His eldest adopted daughter, also named Margaret, a lover of mathematics and medicine, stood in the crowd at his execution. She retrieved his bloodstained hair shirt as a relic to comfort her family and other persecuted believers. Margaret Giggs also is said to have risked her own freedom to help the Carthusian monks who had so inspired her adopted father in his youth. She disguises herself to smuggle in food to ten brothers whom the king was trying to starve into submission. In the end, the jailers discovered the food, Margaret had to stop, and so nine brothers died of starvation (the government hanged the final one). Margaret eventually had to flee into exile, where she died in 1570. She learned her father’s lessons well, as did his other children.

I am blessed to have a father who always tries to teach my siblings and me to do good. Who always treats others with quiet kindness. Who worked hard to support us when we were kids and who taught us how to appreciate the beauty of nature with a fishing pole in hand. Who was there at dinner to listen to us and encourage us. Who took us to church every Sunday to see God. Who loves my mother and still shows us how that kind of love ought to look. Who loves us. And who has a good sense of humor even without the classic dad jokes.

I like the fact that St. Thomas More’s feast day falls near Father’s Day. A good father is a priceless gift, whether a biological father or (as St. Thomas reminds us) another man who cares in holy love for the young people sent into his life whether officially adopted or not. The love a father brings (along with the groans, chuckles, or smiles) can make this world so much better; the example a good father sets can make the next world so much more attainable.

I can’t in good conscience leave a post about a Christian father without a final dad joke… What kind of car did the original disciples drive? A Honda because Acts 2:12 says the apostles “were all in one Accord.” Through the intercession of St. Thomas More, may God bless all dads this weekend. Through our Heavenly Father’s grace, may they always set an example of love, faith, and living with others in holy accord.

If you have a response, thoughts, or questions, please comment at the bottom of the page. Consider subscribing below to get weekly email notifications about new reflections and other news.

Excellent! Happy belated Father’s Day!

Thanks! Same to you!

Give you my facorite dad joke.

What’s the best thing about living in Switzerland?

The flags a big plus

—–from dad jokes