Feast Day: Feb. 3

Ansgar thought they’d kill him. When St. Ansgar (or Anskar), the missionary monk and bishop described in the previous post, began the first sustained attempt to bring the Gospel to Denmark and Sweden, he entered a dangerous world. It was the early 800s—the start of the Viking Age—and Ansgar would spend the rest of his life preaching in the heartlands of those warriors.

Before volunteering for this mission, Ansgar had had a vision of heaven in which God told him to come back as a martyr. One of the reasons that we trust the biography written by Rimbert, his close friend and successor, as an honest record is that both of them worried that this particular vision hadn’t come true, at least literally. Ansgar survived the violence; instead illness took his life. As Ansgar lay on his deathbed, he felt tormented that he hadn’t died a martyr’s death: had he not trusted the Lord enough to risk himself fully? Rimbert comforted his dying friend, saying that Ansgar had done all that could be asked and that the recurring troubles he experienced during those years constituted a kind of martyrdom. Rimbert had a point: the northern lands teemed with danger.

Dangers of the Unknown North: The Dog-Headed Men

To appreciate just how bold Ansgar had been, consider an odd letter that Rimbert received a few years after Ansgar’s death. Ratramnus, one of the leading intellectuals of the day, had written Rimbert to ask him about rumors of a ferocious race of humanoids with the heads of dogs living somewhere along the Baltic Sea. Rimbert wrote back with sailors’ stories that had filtered back to him and then posed a question: what should his missionaries do if the stories were true and they encountered these monsters?

That Rimbert, an intelligent veteran of the region, entertained the possibility tells us how barbarous and terrifying the mysterious pagan north appeared. Perhaps the story started due to secret rituals led by shamans wearing animal masks or hides; perhaps older Greek myths of such creatures had simply spread north. But the story was out there for Rimbert to hear, and it was scary. These beast-people barked and howled rather than speaking and sometimes ate the flesh of dead men. That’s the kind of danger Rimbert and his missionaries were willing to risk.

What is even more interesting is Ratramnus’ response. He said, yes, preach to them. At first he had been inclined to think such creatures to be monsters. Then came Rimbert’s report. Mixed in with stories of animalistic violence, Rimbert reported that these dog-men lived in villages and farmed fields collectively. To live and work together, Ratramnus explained, suggested they had laws and therefore an idea of justice. Agriculture suggested rational planning and an understanding of nature. That they wore some kind of clothes also showed technical skill and therefore rational minds. And even if that clothing was basic, just covering their genitalia, that showed it came from a sense of modesty, which in turn implied a capacity for shame.

Ratramnus concluded that these dog-men were rational and capable of virture. They were humans, not monsters. Therefore Jesus died for them. They needed the salvation a courageous missionary could expound. Regardless of how they looked or even in what violent ways they acted, Christian love was meant for them.

Ansgar and the Vikings

Ansgar never confronted dog-headed warriors, but he did find a world marred by endemic violence. People in the towns where he preached sometimes drove out his missionaries by force and burned their chapels. His biography is full of reference to “pirates”—the Scandinavians who left their farms or fishing to make their fortune by theft, pillage, rape, and enslaving others. Those men were the Vikings.

On Ansgar’s first voyage, Vikings attacked his ship before he even set foot in Sweden and seized all his goods: presents for the Swedish king, books for preaching, and vessels for the liturgy. However, they left him alive and he managed to begin his Swedish mission despite only having the clothes on his back. A later set of colleagues were not so lucky. Vikings ambushed their ship as well and slaughtered them.

Rimbert also tells us how Vikings descended on Ansgar’s home base of Hamburg. Ansgar rushed from room to room, rousing people and telling them to run. He quickly gathered up the most precious relics and books from the church before running after them. Once again, he barely escaped, but the Vikings captured others of his flock and killed or enslaved them.

Yet these are the people Ansgar loved and tried to save. Rimbert said he prayed for the “pirates” even on his deathbed, telling God that these pagans didn’t know any better. He and Rimbert celebrated the small successes. The Scandinavians would at first only seem interested in Jesus if he could do something to help them. If other gods seemed to be failing to protect them, then perhaps they’d agree to try a prayer to Jesus. And if that worked, maybe they’d be willing to repay the Lord with a little fasting, a little almsgiving, and a little listening. Wherever these men and women were at in their lives, Ansgar and Rimbert saw their potential and offered whatever they could.

Dog-Headed People Today

Vikings are long past and happily shrouded in romance. Werebeasts (usually now more sexy than bloodthirsty) only roam the pages of fantasy novels. Do Ansgar’s dangers still have any relevance to the modern world? Unfortunately, yes. Every single year, governments and terrorists still kill priests, nuns, and missionaries. One organization claims that 5,621 Christians were killed worldwide in 2022 for reasons related to their faith.

Moreover, despite having very human heads, many people have had their very humanity denied. Conquistadors claimed that Native Americans could be exploited like animals since their inferior technology showed they hadn’t reached true human rationality; Pope Paul III in 1537 had to officially declare that they were indeed human and forbid their enslavement. In the 1800s and 1900s, scholars developed a scientific system of classification for the human species based on race that worked specifically to strip human dignity from Africans. You could go to “human zoos” in places like Belgium to see actual Black people in reconstructions of their “native habitat.” Visitors gawked at them from behind fences while signs reminded the “enlightened” Europeans not to throw peanuts. Today, the abortion debate largely centers on whether or not the kick a pregnant mother feels in her womb is from the foot of a human child or from a random clump of cells without inherent value.

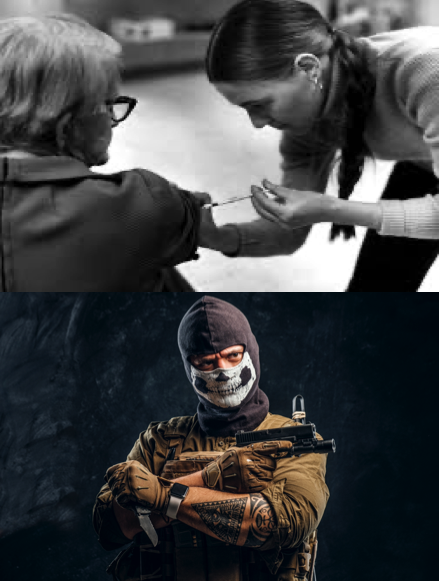

Human dignity is a daily issue. Sometimes this can be subtle, as when an elderly woman’s complaints are pooh-poohed by a doctor and she is talked about as though she isn’t even in the room. Other problems are systematic. The Catholic Church tries to preach a “consistent life ethic”: uphold the dignity of every person at every time. Can you love and respect people of different races and religions? The elderly and the dying? Immigrants? Welfare queens? Drag queens? Rapists, murderers on death row, and terrorists? Could you go up to someone who hates you and just look them in the eye with love despite their vitriol and threats? Would you help them? Would you also challenge them when they are in the wrong? Would you love them? Even if they refused your help? Even if they hurt you again?

If you can answer yes to all those questions without hesitation, you are doing better than me (and most Christians, including Christian leaders). That extreme love, however, was Ansgar’s life’s work. That’s the work that Rimbert and Ratramnus tried to continue.

In looking at another person, they saw beyond the exterior mask to see the rational, vulnerable, human soul for whom Christ died. And then, despite the dangers, those saints loved.

If you enjoy these posts, there is a subscription box below to get notifications whenever a new reflection is posted. If you have a response, thoughts, or questions for me, please feel free to comment below (just keep it charitable)!

2 Responses

[…] How valuable is a single soul? According to legend, you could sell yours to the Devil for power and women like Dr. Faust or rockin’ guitar skills like legendary blues musician Robert Johnson. Of course, they’re just stories and most such stories make the same point—anything you can dream up as the price of your soul dramatically undersells yourself. I’d like to reflect a little on the the worth of your soul today with the story of St. Ansgar, the Apostle of the Swedes, Danes, and Vikings. (Part 1 of a two-part reflection). […]

[…] Holy Land or perhaps he came from a foreign land of monstrous men, perhaps even cannibals with the heads of dogs. He was a freak of nature, stronger than others with a fierceness to match. Proudly considering […]