I feel guilty if my bird feeder runs empty in the winter. I suppose it’s silly. After all, birds have survived thousands of winters without people putting out food. I’ve only fed the ones in my backyard for a few months so surely they could continue the proudly wild tradition of their avian forbearers. So why do I go out in the snow and bitter chill to fill their feeder with sunflower seeds?

At a basic level, I find birds beautiful. I enjoy seeing the bright red of the cardinal and the cute white-black puffball of a chickadee. Beauty should be cherished and nourished, especially when it is fragile (chickadees live only two or three years on average, although they could live for a decade if spared the perils and hardships of the wild).

Yet I go outside to feed them even when I won’t see them. I double-check their seed supply before leaving for holiday travel—precisely when I won’t be there to watch. So why feed birds? A Christmas carol has been playing in my head as I’ve gone out and, oddly, I think that this song—plus the little matter of God becoming human—may be my answer.

The Origins of St. Wenceslaus

Duke Václav of Bohemia only came to my attention and that of most Americans through an odd quirk of Christmas fate. He was an important man for his own country (now the Czech Republic). He strengthened the government and promoted Christianity in a place where paganism still lingered. In stories of him, his hospitality and charity to the poor particularly stand out. Yet politics cares little for charity. His own brother, in a successful bid for power, assassinated Václav in 935 AD.

Václav’ people recognized him as a saint, and his brother would go down in history as Boleslaus “the Cruel.” The emperors who later ruled the area posthumously elevated him to the status of a king and, as his fame spread in the region, he became known as King Wenceslaus the Good.

The Carol of the Good King

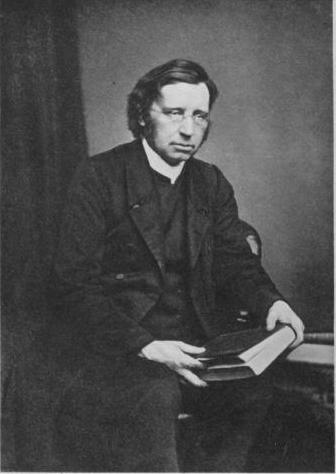

Václav, or Wenceslaus, would have remained little known outside Central Europe except for a remarkable Anglican priest named John Mason Neale in the 1850s. Neale’s passions consisted of charity, hymns, and the Christian traditions of the Greek and Slavic half of Europe. He helped direct an almshouse for the poor and founded an Anglican order of women dedicated to serving the sick—an act which led to hatred, death threats, and physical beatings by radical Protestants who saw that religious life as a betrayal of Anglican belief.

As part of his interest in the diverse heritage of Christian Europe, Neale translated many hymns into English including a collection for Christmas. This collection included his adaptation of a Czech poem’s fictionalized celebration of Václav’s charity: “Good King Wenceslaus.” It is one of those carols that most people vaguely know, but isn’t part of the staple playlist. I like it, but it has a disadvantage compared to most carols: the first verse doesn’t stand on its own and most people only know the first verse of a carol.

Good King Wenceslaus looked out, on the Feast of Stephen, When the snow lay round about, deep and crisp and even; Brightly shone the moon that night, tho' the frost was cruel, When a poor man came in sight, gathering winter fuel.

Even if you know the Feast of St. Stephen is December 26, so what? What does this mean? If, however, you go through all the verses, you have a simple, worthwhile story. The saintly Wenceslaus springs to his feet and dashes out into the bitter cold with his serving page to bring the poor man in from the cold to share the king’s own feasting. It is a night where the dark chill bites to the bone. The page wants to turn back, but the saint urges him on in charity; just follow in my footsteps, he says. And suddenly the task changes for the page:

In his master's steps he trod, where the snow lay dinted; Heat was in the very sod [soil] which the saint had printed. Therefore, Christian men, be sure, wealth or rank possessing, Ye who now will bless the poor, shall yourselves find blessing.

The King, the Incarnation, and Charity

The page finds a blessing of comfort and strength following his lord in the night. Who is the master in whose footsteps we follow? Christ. The saint imitates our Lord, and we can follow him. Even when the environment around is unpleasant or even deadly, there is a comfort in following Jesus and the path of charity. There is blessing. If not, would Neale have persevered in his own work despite the beatings and threats?

A mighty king who jumps up from his own table into the cold because he feels compassion for an ordinary pauper is a wonderful image of Christ. Of course, the gap between two people (one of whom people think is more important) is nothing compared to the gap between the eternal Creator of the universe and short-lived, fragile humankind. Yet Christ crosses it at Christmas. He loves us even in the bitter cold this world sometimes brings.

Can I do that? I’ve never invited a poor man into my house for dinner. I donate to food banks and soup kitchens, but there’s always a safe distance between me and the needy that doesn’t risk “contaminating” my home. I’m not a saint.

Feeding the Birds

But I do feed the birds. It’s not much. It’s something. I recently came across a quotation: “Feeding the birds is also a form of prayer.” There’s truth to it. Feeding the birds is a way of “practicing” charity. I delight in the birds for their sake because I see the fragile beauty of their creation and know they are precious in God’s eyes (Mt 6:25-30; 10:29-31). I care for them whether or not I gain something in return, though I rejoice when they do become part of my life. If God, who is beyond anything I can imagine, can care for creatures like me, then I can honor and imitate Him by caring for “lesser” creatures too.

Feeding the birds is also a form of prayer.

Pope Pius XII

I don’t know why it is sometimes easier to be charitable to birds than people, but it can be. I hope though that being charitable in this small way helps make my other charity stronger even—or especially—when it involves trudging out into freezing wind and snow. Maybe feeding the birds makes me appreciate God’s charity to humanity a little more. And maybe that can help me love the people around me in need, even when the sacrifice is uncomfortable. I hope so.

Ya got me thinking about Mary Poppins…and the bird lady…

“Come feed the little birds, show them you care

And you’ll be glad if you do

Their young ones are hungry, their nests are so bare

All it takes is tuppence from you”

All around the cathedral, the saints and apostles

Look down as she sells her wares

Although you can’t see it, you know they are smiling

Each time someone shows that he cares