Feast Day: March 3

Growing up, I had to endure ice cream-free Lents. My whole family did. I think my mother suffered the most since she loved that dessert, but she was the one who had chosen our Lenten sacrifice so she couldn’t complain (at least not counting the occasional wistful remark on how much she looked forward to bittersweet ice cream pie on Easter Sunday).

One thing that I value about my family’s Lenten tradition is that my parents didn’t leave this fasting in an isolated limbo. If our parish distributed a short Lenten reflection prayer book, we’d take turns reading it aloud after dinner in place of dessert. At the end of Lent my mother took us kids to the grocery store and we’d run around grabbing canned goods for the local food pantry using the money we’d saved from not eating ice cream.

In retrospect, I think my mother cheated a little and put in more money than we had actually saved, but it was a wonderful lesson. The root of almost everything Christian is love of God and love of neighbor; prayer and almsgiving enrich our fasting with that double love which is why the Church almost always brings them together.

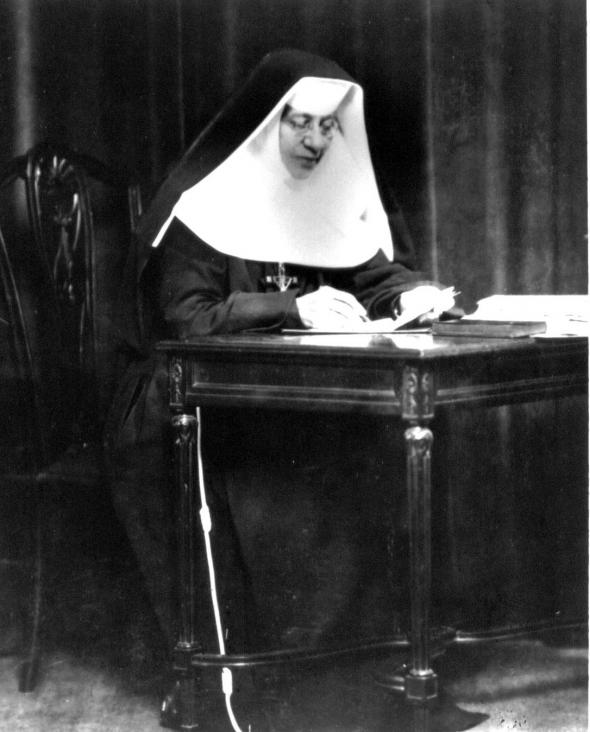

I’ve been remembering my parent’s nurturing of our family’s spiritual life because of St. Katharine Drexel, the only officially canonized saint born in the USA. In 1888, this Philadelphian millionaire gave up her fortune to spent the rest of her life as a nun serving Black and Native Americans (including support for Fr. Gus, America’s first Black priest). It was an extraordinary, mind-boggling act. What brought her to it? In a word, her parents.

Raised for Charity

Parents are our primary educators—particularly educators about faith. The family is the domestic church. As a Catholic educator, I repeatedly heard the Church push these ideas. The Drexel family lived them.

Every evening, Katharine’s father Francis retreated for half an hour of uninterrupted prayer. Three times per week, her stepmother Emma would literally open the family home to needy Philadelphians and gave out food, clothing, and rent money. Katharine and her sisters helped as they grew older. “Charity” comes from the Latin word for “love” and the Drexel’s lived that. Katharine’s parents also supported churches and donated to causes, but what resonated with Katharine and her sisters was how Christian love found a concrete place in the heart of their home.

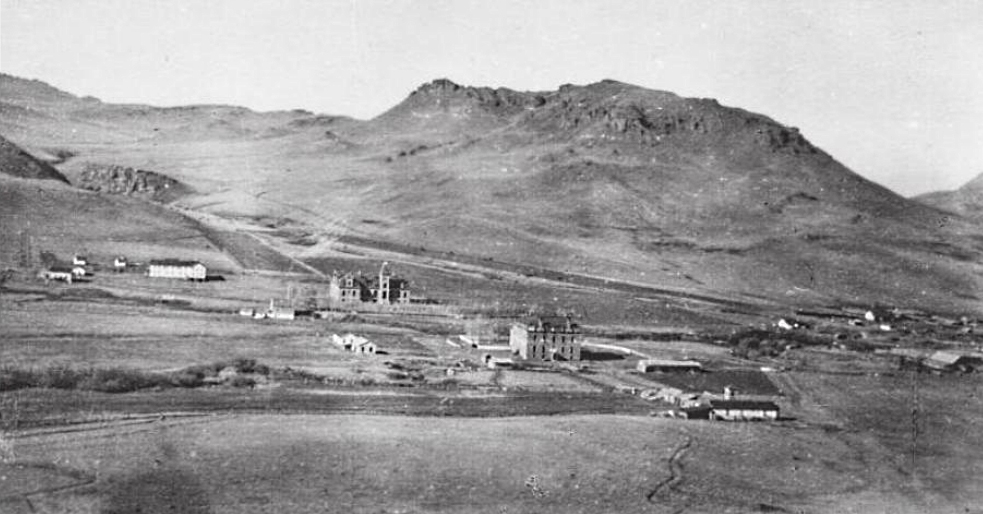

Her parents also didn’t shy away from uncomfortable discussions about race. In particular, a Western vacation—during which the family saw the poverty in which many Native Americans lived—opened Katharine’s eyes to racial injustice in the USA. Many Great Plains tribes had been conquered, deprived of the great buffalo herds, and forced on to reservations just a few years prior. When her parents died, Katharine and her sisters inherited over $15 million (at a time when an unskilled laborer might earn $500 per year). All three agreed that they would use that money in a way that honored their parents: putting it at the service of Black and Native Americans, particularly in the form of education.

After a couple years of the three coordinating this financial charity, Katharine’s life took a turn. When the sisters visited Pope Leo to ask for missionaries to staff the new schools, he asked: why not her? Katharine balked. She found religious life attractive, but could she (with her admittedly pampered background) really endure the hardships of life among the poorest and most despised Americans? It was a fair question. It’s not uncommon for well-meaning young people to join programs today like Teach for America and walk away shellshocked a year later.

Strength for Charity

In the end, Katharine’s spiritual director not only convinced her to take on that role of missionary educator but also to found an order dedicated to serving and educating minorities in America in 1891. We are richer for it. By the time she died in 1955, St. Katharine had helped found over sixty schools and missions in seventeen states ranging from New York’s inner city to the Great Plains down the Mississippi to New Orleans and the first Catholic university of Black Americans: Xavier University of Louisiana. Her sisters ran over half of these foundations.

What sustained her? The first clue is in the name she chose for her order: the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament. She began with prayer. Eucharistic adoration, in which Katharine contemplated God making a total gift of Himself to us, inspired her to give herself in turn to others.

The role of community and family also played an important role. Her biological sisters, her religious sisters, and sympathetic priests and bishops all gave her supportive human relationships to help her through the hard times. And there were hard times, as groups like the KKK met her initiatives with hostility and even violence. She saw several of her foundations burned to the ground.

That may have made her more determined. Her initial sense of compassion for the downtrodden condition of minorities developed into a fierce passion for social justice. She couldn’t stand seeing people’s humanity belittled and denied. One of my favorite Katharine stories is about the dedication of a building at Xavier University. Locals in New Orleans warned her that white folk had to be seated first at the ceremony. “Fine,” she said. When people showed up at the dedication, they found that all the chairs had been removed and everyone, regardless of skin color, had to stand in the crowd mixed together for the ceremony. She was a formidable woman who found ways to get good work done in spite of the obstacles.

The Drexel Family and Almsgiving in our Lent

As we continue our journey through Lent, St. Katharine’s feast day is a good reminder to examine our individual and family practice of charity. Are we willing to give our treasure and ourselves? Are we teaching others, especially our children, to do so too?

If I can offer one piece of advice, it is this: give with love because that is what charity means. The traditional Christian term for giving to the poor is almsgiving, which comes from a Greek word for mercy. As patristic and early medieval preachers liked to remind their congregations, Jesus said that even giving a cup of cold water in his name would earn a prophet’s reward (Mt 10:42)—just do it with a willing heart. Everyone has something to give. Maybe it’s millions of dollars. Maybe it’s only loose coins but you give them with a smile and a “how are you?” to a homeless beggar. Maybe it’s calling up a lonely relative and talking for an hour.

If the time, money, or emotional support that you give has value to you and to the other person, then you’re doing well. If you’re giving leftovers you don’t care about or you haven’t given a thought to the person receiving them, then you may be missing the opportunity for genuine charity.

Like St. Katharine, pay attention in particular to those who others might pass over. That is where love is needed the most. That may also lead you to important, uncomfortable questions about justice. If it does, I think St. Katharine might be a good person with whom to discuss the answers.

If you have a response, thoughts, or questions, please comment at the bottom of the page. Consider subscribing below to get weekly email notifications about new reflections and other news.