Feast Days: February 13 (Blessed James Miller) and July 28 (Blessed Stanley Rother)

Two Americans died in Guatemala when I was a child. Stanley Rother and James Miller, two simple American farm boys, had discovered a deep love inside themselves that called them to serve their brothers and sisters abroad in Christ’s name. As a consequence of that love, they died as martyrs, the first American citizens to be officially recognized by that title.

I want to think of martyrdom as belonging to distant countries in a heroic past. I want to believe that the hatred for Christians is something a modern, civilized world has outgrown. I know though that this isn’t true. More Christians died for their faith in the twentieth century than any previous century. I’ve read enough newspaper articles about persecutions in places from Nigeria to India to know that this century isn’t likely to be better. There is even hatred for the Church in my own community. Ironically, the death of faithful Christians like Blessed Stanley Rother and James Miller is what gives me hope in the face of the hatred that killed them.

Blessed Stanley Rother: A Priest for His People

Stanley Rother almost didn’t become a priest. He flunked out of seminary due to his struggles with Latin. The priests of his Oklahoma diocese didn’t give up on him. They encouraged him, tutored him, and then sent him to Mount St. Mary’s seminary in Maryland. There he squeaked by and became Fr. Stan. In 1968, after five years of ministry in Oklahoma City, he asked his bishop to assign him to the poor parish in Guatemala that his diocese supported.

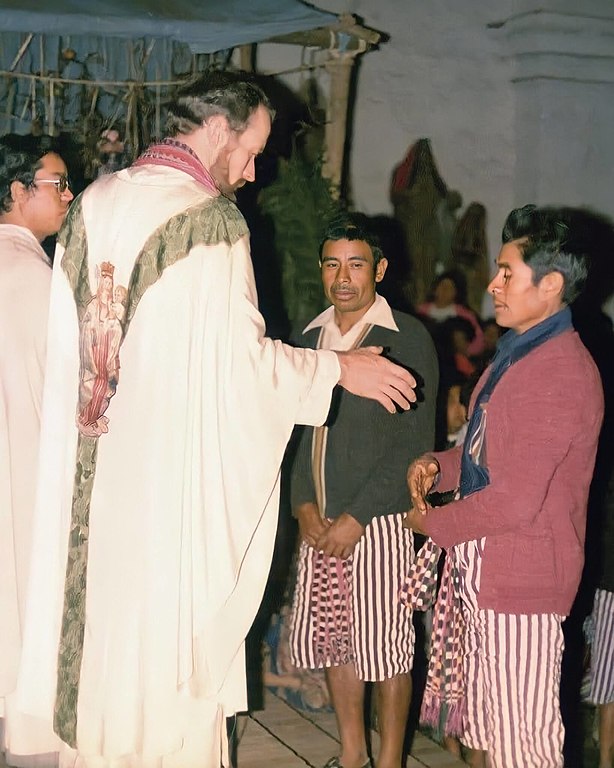

On arrival in his new parish of St. James in Santiago Atitlan, Fr. Stan found a place of tremendous beauty, deep poverty, and widespread opportunities to love. Santiago Atitlan sits in the inner highlands of Guatemala on a magnificent crater lake surrounded by jagged peaks. Most of the people living in this isolated region belonged to the native Tz’utujil people, descendants of the Mayans. Unlike most newcomers to the region, this priest—who had struggled to learn Latin—mastered both Spanish and the more difficult native Tz’utujil language. Quickly a mutual bond of love and respect grew between people and pastor.

When Fr. Stan arrived, half the children in his parish died before the age of six. Fr. Stan worked hard to change that. With the support of donors back in the USA, he dug wells, built a hospital, introduced new farming techniques (he had grown up on a modern American farm after all), and founded a radio station to spread knowledge. Child mortality dropped. Quality of life increased. Any secular NGO would have felt pride at his accomplishments; but Fr. Stan and his people knew that this development work formed only part of a wider Christian mission. Quality of life meant building up spiritual riches as well. Fr. Stan spent even more time serving his people in prayer, the liturgy, and religious education than he did on mere material needs. He even translated the New Testament into the Tz’utujil language.

That Christian love for his flock is why he couldn’t stay silent during Guatemala’s civil war. To combat the rural Marxist insurgents, the government sent the army into the hinterlands including Santiago Atitlan. There the military waged a brutal campaign in the shadows, encouraging informants, assassinating or arresting people based on a single whispered rumor, and conscripting the young men. Fr. Stan spoke up. He politely but firmly asked why parishioners disappeared. He buried those killed by the military and cared for their widows and children despite knowing the dangers of associating with “criminals.” He allowed one parish catechist on the death list to hide in the rectory.

In 1981, warned that he had been marked for death as a supposed enemy of the government, Fr. Stan left the country and returned to the USA. Publicly, he expressed hope that these troubles would simply blow over. Privately, he spent hours in anguished prayer before the Eucharist or at the Marian grotto at his old Maryland seminary. At the end of a week’s retreat at his old seminary, he told one mentor:

I know what I must do. If I go back and speak, they’ll kill me. But if I keep silent, what kind of a Shepherd would I be?

Fr. Stanley Rother, according to a friend at Mount Saint Mary’s, Emmitsburg, Maryland

In private letters, he repeated that “the shepherd cannot run at the first sign of danger. Pray for us that we might be a sign of the love of Christ for our people.” No one forced him to go back. Fr. Stan chose to return to his people, knowing he might have to lay down his life like the Good Shepherd he followed (Jn 10:11). And he did. On July 28, 1981, three men broke into the St. James rectory to drag Fr. Stan away. He refused to leave and, with all the strength of a big American farmer, he held on to the door frame. The men, literally unable to remove the priest from his parish and people, shot him in the head.

Blessed James Miller: A Teacher of Courage and Love

James Miller, a De La Salle Christian Brother and teacher, had a similar vocation to help the poor discover a better life, both materially and spiritually. Like Fr. Stan, he grew up on a farm (although in Wisconsin rather than Oklahoma). He did better academically than Fr. Stan had, though James had a reputation for being perpetually late (a habit, Cardinal Lacunza of Panama remarked, which made him fit right in with Central American culture). He began his ministry in the USA as a teacher and football coach, but felt a call to serve marginalized people in Central America.

Br. James worked in Nicaragua first, until the Socialist Sandinistas seized power. Worried that they would target Br. James for his work with the previous government in founding new schools, the Christian Brothers recalled him in 1978 for his safety. He wanted to return to Central America, so they assigned him to Guatemala.

There he and the other priests and brothers in his town found themselves confronted by the same violence and injustices as Fr. Stan. Since many of their students were legally exempt from conscription, Br. James and his companions had the ability to intervene when the military picked one of their boys off the street to impress into the army. They quickly became pests in officials’ eyes. These officials saw their legal activism and their Christian concern with educating the poor as evidence of Marxist sympathy—ironic, in the case of James, who had fled a Socialist government in Nicaragua only a few years before.

Br. James knew his danger. When asked if he felt fear in light of the violence around him, he joked, “Are you kidding? I never thought I could pray with such fervor when I go to bed!” Privately, he wrote his cousin, “The level of personal violence is reaching appalling proportions (murders, tortures, kidnappings, threats, etc.) and the Catholic Church is being persecuted because of its option for the poor and oppressed. God knows why He continues to call me to Guatemala when some friends and relatives encourage me to pull out for comfort and safety… I place my life in His providence; I place my trust in Him.”

His faithfulness to God’s call led to his death. On Friday, February 12, 1982, a government friend warned the brothers in their communal residence that one “sub-director” had been marked for death. Three of them, including James, had a “sub-director” title. They talked and prayed far into the night. Finally they decided that this was their ministry and their people. They would stay. The next day, Br. James took his students out for a picnic. When they returned, he propped a ladder against the side of the school and climbed it to replace a broken light. Four hooded men drove up and opened fire with submachine guns. Br. James’ bullet-riddled body fell to the ground.

The Power of Vocation

Both Fr. Stan and Br. James knew whom God called them to be. A priest and shepherd. A teacher among the poor. In their vocations, they found their true selves. They found purpose. They found love, both human and divine. They found something worth dying for. No wonder the powerful in this world found these two men frightening and tried to eliminate them.

“Tried” is the key word. Fr. Stan and Br. James both risked their lives knowing that, in losing their lives for God and their people, they would find eternal life. Even here, in this world, their influence lived on—in Guatemala, in Oklahoma and Wisconsin, and then across the church. The parish in which Fr. Stan labored was founded in 1547 and had never had a single person answer the call to the priesthood before 1981. After Fr. Stan’s martyrdom, nine men from that single parish have received ordination and another seven are in seminary training. Killing Fr. Stan didn’t scare people away from following the Christian life. Rather, it made them want to be Christian shepherds like him.

I’m not sure that vocation can exist without sacrifice. Priests and religious sacrifice through obedience, celibacy, and poverty. Married couples sacrifice in their care for one another, the hard work of raising children, and simply through learning to live with another very imperfect person. Vocations to particular kinds of service from teaching to firefighting may cost in time, emotional investment, or lost income, and might even involve risking one’s life. What makes these sacrifices worthwhile is love of neighbor and love of God. Those who, like Fr. Stan and Br. James, follow through on their joyful embrace of sacrifice and vocation, will “receive back an overabundant return in this present age and eternal life in the age to come” (Lk 18:30).

Blessed Stanley Rother and Blessed James Miller, pray for me, that I may have the courage to become who I am truly called to be and pray that I have enough love to sacrifice for it so I may receive true joy on Earth and in Heaven.

If you have a response, thoughts, or questions, please comment at the bottom of the page. Consider subscribing below to get weekly email notifications about new reflections and other news.